VIPs

- Both the MoM and YoY changes in the CPI and core CPI exceeded every estimate by economists in Bloomberg’s survey; the surprise generated an up-shift in the U.S. Treasury curve, with the greatest bulging seen at the 5-yr point as the 5s30s curve flattened < 70 bps

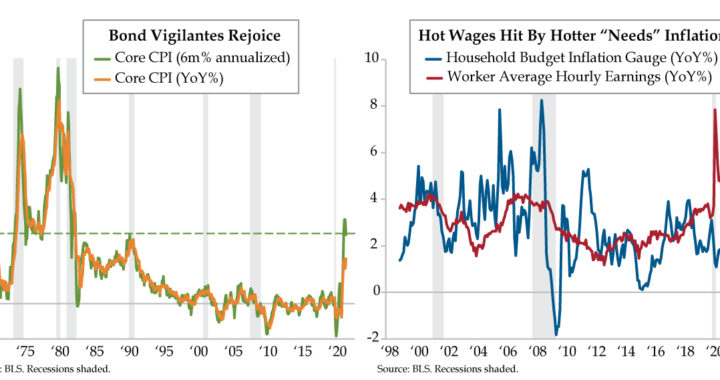

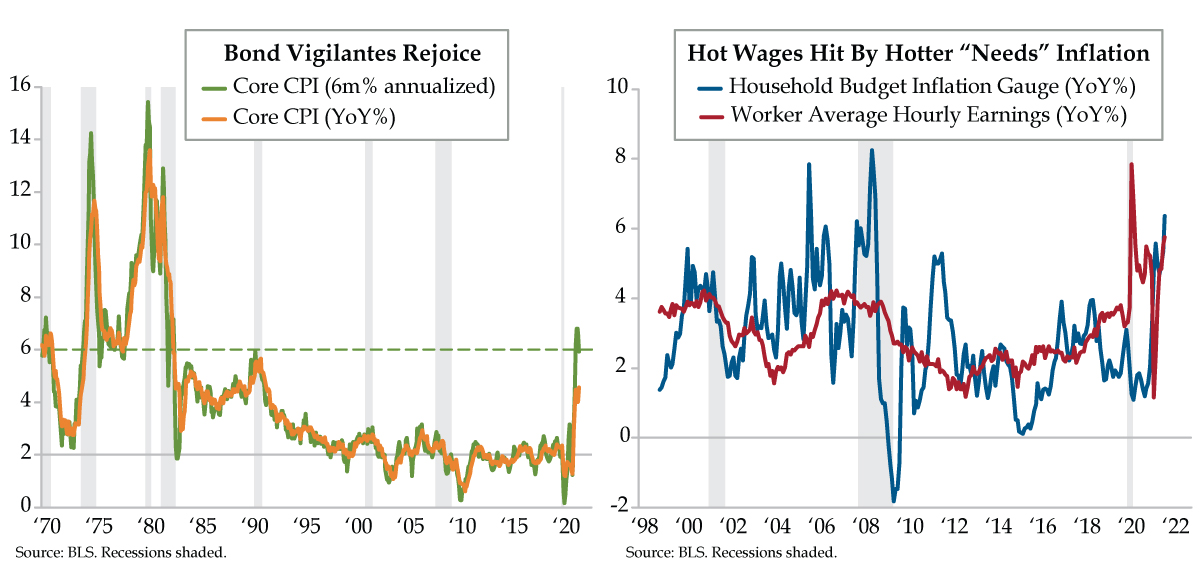

- In the last five months, six-month annualized core CPI has run between 5.9% and 6.8%, not seen since the early 1980s; with this shorter-run trend running hotter than the YoY pulse, core CPI inflation forecasts are likely to be revised upward from the current 4.6% annual rate

- QI’s Household Budget Inflation Gauge rose to a 6.4% YoY rate in October, the highest since the Great Recession; while wages for non-manager workers has risen from April’s 1.1% to 5.8% YoY in October, the HBIG has outpaced wage gains in five of the last seven months

The Declaration of Independence is the philosophical foundation of American freedom. Of course, it’s U.S. veterans who have protected these freedoms we cherish so. Veterans Day pays tribute to all who’ve honorably served in the armed forces but gives special thanks to those who are still with us. Today’s Federal holiday originated as Armistice Day on November 11, 1919, the first anniversary of the end of World War I. Major hostilities of the Great War were formally ended at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, when the truce with Germany went into effect. Congress passed a resolution in 1926 for an annual observance and Veterans Day became a national holiday in 1938. It wasn’t until 1954 that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, one of the most decorated veterans in U.S. history, officially changed the name from Armistice Day to Veterans Day. For part of the 1970s, Veterans Day was celebrated on the fourth Monday in October. But, due to the historical significance of the date, in 1975 President Gerald Ford sagely returned the holiday to November 11.

Nowadays, references to the 1970s have inflation connotations attached to them. Yesterday’s consumer price index (CPI) clearly qualifies for that characterization, and not just because the forecasting community was caught completely offsides…again. It wasn’t so much that the month-over-month and year-over-year (YoY) changes for both the CPI and core CPI smashed through consensus estimates. It was that every estimate by every economist in Bloomberg’s survey for all four measures fell shy of the official results.

Bond vigilantes assemble! The surprise factor from the CPI generated a level-shift up in the U.S. Treasury curve as shorts were likely fleeced on the back of last week’s rally in the bond market. The bulge was greatest in the belly of the curve, at the 5-year point, generating additional flattening in the 5s30s curve under the 70-basis point mark.

Moreover, both inflation breakevens and real yields rose, the former by more than the latter. Earlier in the trading session, most of the move in nominal yields was driven by inflation expectations, as rates traders adjusted to the reality of higher inflation. Later in the session, vigilantes pushed up real yields, building in a Fed boxed tighter into a corner of its own making. To that end, Fed fund futures priced in one quarter-point hike by July 2022’s FOMC meeting and more than two by the December meeting.

Back to those 1970s references… Nothing gets bond bears more lathered up than an inflation comparison to the bell-bottom decade. As you see on the left, in the last five months, the short-run core CPI inflation trend (six-month annualized) has run between 5.9% and 6.8%. These elevated rates also prevailed in the 1970s. From the early 1980s to (what was the) present, these levels were seen as the ceiling for the short-run core trend.

This narrative will feed on itself, giving bears more ammunition. The short-run inflation trend (six-month annualized) is running above the medium-run path (year-over-year), and the latter usually converges to the former. Core CPI inflation forecasts are likely to be chased up from today’s 4.6% annual rate. And core inflation is the operational target for the Fed – it captures the underlying inflation dynamic by wiping clean those (most meaningful but volatile) food and energy prices that can be subject to supply shocks, geopolitical risks and acts of God.

Playing devil’s advocate: What if the Fed was right in letting inflation run hot? Conventional wisdom and yesterday’s bond market reaction suggest the answer is a decided ‘no’. But what if the kind of inflation that’s brewing was damaging consumer purchasing power, future consumer spending prospects and thereby endangered the Fed’s maximum inclusive employment mandate?

Many moons – Feathers – ago, we introduced the concept of the Household Budget Inflation Gauge (HBIG). Quite simply, it’s “Needs,” or nondiscretionary, inflation. Think of a typical household budget — a compilation of prices for food & beverages, energy, clothing, household supplies, housing services, utilities, health care, home/auto/health insurance, phone/TV/internet, higher education and personal care products & services.

In October, the HBIG rose to a 6.4% YoY rate, the highest since the Great Recession. Applying our favorite normalizer, the z-score (deviation from the mean adjusted for volatility), the October HBIG translated to a 2.1 on the z-scale. Of the seven other documented precedents, five were either leading up to or during the 2007-09 recession or after the massive distortions that came ashore in 2005’s Hurricane Katrina.

A high and rising HBIG is more damaging to household budgets down the income stack. Worker wage inflation from the 80% of employees that are not managers proxies and has run up from April’s 1.1% annual rate to last month’s 5.8% YoY pace; the HBIG has outpaced wages in five of those seven months, October included.

Any veteran can tell you that Needs inflation cannot be avoided. The bond market has been conditioned by the Fed to sell the upside news of upside inflation surprises. The thing is, if the HBIG was the operational inflation target, the Fed should react in opposite fashion – lean easier, not tighter. Based on last week’s signaling from Powell & Co. that it’s not “a good time to raise interest rates…because we want to see the labor market heal further,” the Fed may be inadvertently doing just that.