VIPs

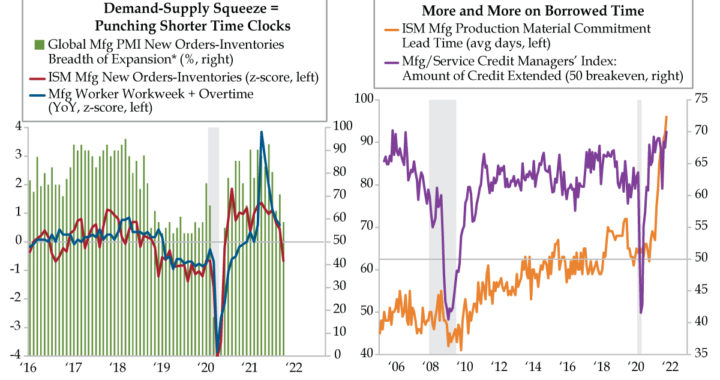

- The ISM New Orders-Inventories spread shrunk to 2.8 in October, the lowest since last year’s re-opening; as a z-score, this is below trend at -0.67, and mimics the rest of the world, with only 59% of major economies seeing spread expansions, the worst since June 2020

- The factory workweek plus overtime collapsed from 45.7 hours in February 2020 to a low of 41.3 hours in April amidst pandemic shutdowns; since recovering in January, performance has been up-and-down, before settling just below January’s print at 45.6 hours in September

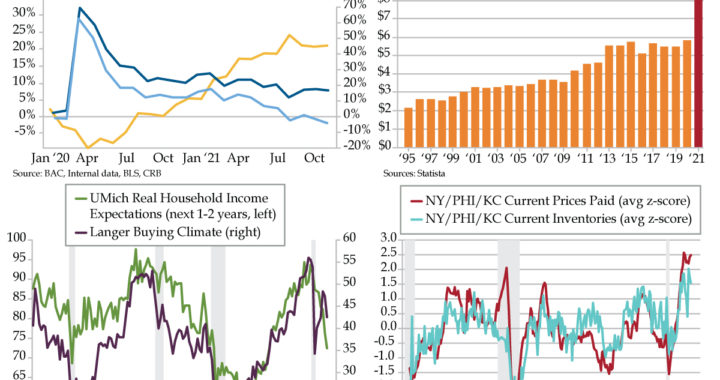

- ISM’s lead time commitment for production material advanced to 96 days in October from September’s 92 days; higher upstream costs have manifested into a near-record level of credit extension, with the NACM’s Credit Managers’ Index registering a 70.0 print in October

About 30 miles southwest of Syracuse in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York sits a small city rich in American history. Auburn, New York has been dubbed “History’s Hometown” as it’s a hub of key figures, events and culture with attractions pertaining to the Civil War era, the Underground Railroad and the birthplace of talking films. Even the 1888 invention of the time clock is linked to an Auburn jeweler — Willard Le Grand Bundy. He patented his design two year later and he and his brother, Harlow, thus formed the Bundy Manufacturing Company to mass-produce time clocks. In 1900, the time recording business of Bundy Manufacturing, along with two other related businesses, consolidated into the International Time Recording Company (ITR). In 1911, ITR, Bundy Manufacturing, and two other companies were amalgamated (via stock acquisition), forming a fifth company — Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). Ultimately, it would change its name to International Business Machines, better known today as IBM.

Time clocks, or punch clocks, usually were reserved for hourly workers to record their toiling in manufacturing and service occupations. Employees punched in to start their workday and punched out to end it, sometimes with the asterisk of overtime hours being documented. This Friday’s U.S. employment report for October will provide the latest update for the private nonfarm economy.

Each month, only the most cyclical industries in manufacturing provide a prism into both average weekly hours and average overtime hours. No other private sector industries report this level of detail to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The COVID-19 shock saw the factory worker workweek plus overtime collapse from 45.7 hours in February 2020 to a cycle low 41.3 hours in April 2020. Nine successive monthly gains later and full recovery was achieved in January 2021. Since then, however, the performance has been anything but streaky. Ups and downs have punctuated 2021; by September, this metric stood marginally below where it started the year, at 45.6 hours.

For cyclical indicators, a bumpy ride typically foreshadows a turn in the trend. Judging from the relative distance between demand and supply for forward guidance, there is a greater risk that hours get lowered than raised. This read can be gleaned monthly via the new orders to inventories spread in manufacturing from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). At face value, the spread compressed to 2.8 in October, the lowest since the involuntary bounce back occurred after the height of the pandemic, in Spring 2020. Over the last several years, a reading like this, however, would be considered below trend, at -0.67 (red line) – the context for which is attained by applying our favorite normalizing z-score process (deviation from the mean adjusted for volatility).

The new orders-inventories spread gauges near-term output prospects, which carries over into predicting working hours. A wider spread suggests stronger activity and longer hours to get the job done. When the combination of orders-inventories compresses, as is the case today, this bearishly indicates fewer labor resources are required. The easiest “fix” is adjusting hours. The normalized year-over-year trend in the production workers’ workweek plus overtime (blue line) looks set to slide below trend just like its ISM guide.

The global environment provides a backdrop for the narrative of punching shorter time clock hours which can be observed across the mosaic of global manufacturing purchasing manager indices (PMIs). Of the 41 countries we track, the breadth of expansion in new orders-inventories has declined to 59% so far in October, the least positive performance since June 2020 (green bars).

ISM expounded at length “that their companies and suppliers continue to deal with an unprecedented number of hurdles to meet increasing demand. All segments of the manufacturing economy are impacted by record-long raw materials lead times, continued shortages of critical materials, rising commodities prices and difficulties in transporting products. Global pandemic-related issues – worker absenteeism, short-term shutdowns due to parts shortages, difficulties in filling open positions and overseas supply chain problems – continue to limit manufacturing growth potential.”

Persistently elongated lead times increasingly slow the production process. Look no further than ISM’s lead time series for production material commitments. Last month, we noted that the time it took to acquire these key inputs rose to an average of 92 days in September, comparing only to the longest postwar lead times encapsulating the 1973-74 period. October offered no relief — this metric advanced to 96 days (orange line). Reading truckers’ anecdotes suggest the prolongation will persevere as the supply chain’s disruptions don’t get resolved until well into 2022, regardless of whether demand plummets in the interim.

Lead times echoing the 1970s inflation era translate into the need to attain higher leverage as the most cyclically exposed industries’ budgets get busted. The risk is that it flows down the distribution chain to service industries with the highest supply-chain exposure. The purple line depicts how the higher upstream cost backdrop has manifested itself into a near record level of credit extension (70.0 on a 50 breakeven) across both the manufacturing and service sectors, according to the October National Association of Credit Management Credit Managers’ Index.

Time clocks look set to get punched with shorter workdays as worsening vendor performance moves in gray clouds over the short-run industrial outlook. Expect the collective of the Street forecasting community to roll out the catchphrase “mid-cycle slowdown” to describe this episode. A better characterization would be the new darling term of “bottleneck recession.”