VIPs

- The unemployed have fallen by 1.8 million in the last three months, a decline that compares solely to 2020’s post-pandemic reopening; permanent job losers are down by 936,000 and account for more than half the improvement, a confidence vote for a sustainable expansion

- While September’s gain of 194,000 jobs disappointed, education headcounts fell while total private employment rose by 317,000; though 4.8 million jobs remain to be recovered, the yield curve steepened, signaling the Fed should be on track to launch its taper in November

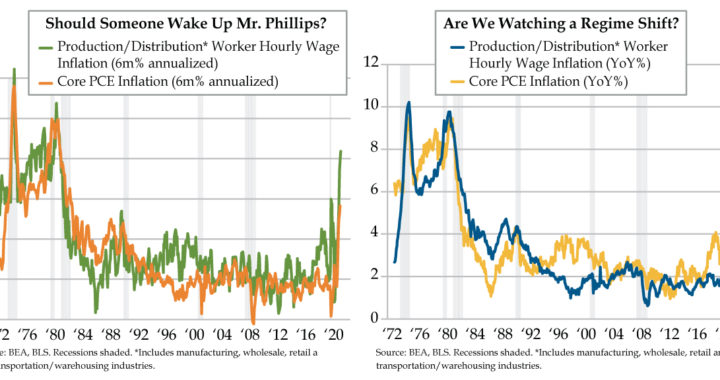

- Wages for production/distribution workers have seen an 8.4% annualized gain in the six months ended September, the highest since the early 1980s; small businesses are also feeling pressure, per Paychex, seeing three-month annualized gains between 5.2% and 5.4%

Levi Hutchins lived firmly by one rule: Wake before sunrise – 4:00 a.m. to be exact. Listening to the early bird inside his head, this American invented the mechanical alarm clock in 1787. Of his design, he said, “It was the idea of a clock that could sound an alarm that was difficult, not the execution of the idea. It was simplicity itself to arrange for the bell to sound at the predetermined hour.” It would seem Hutchins was more interested in beating the rooster than benefiting monetarily — he never secured a patent. And though a half a century on, Frenchman Antoine Redier did patent an adjustable alarm clock, it didn’t make it across the ocean leaving American Seth E. Thomas to stake legal claim to his own version in 1876. His eponymous company mass-produced the alarm clock, delivering the innovation to the general public and putting roosters out of business once and for all.

Speaking of unemployment lines, they’ve shortened considerably. July, August and September yielded decreases in the total unemployed of 782,000, 318,000 and 710,000, respectively. The three-month cumulative 1.8-million decline compares solely to 2020’s post-pandemic reopening. Permanent job losers, down an unmatched 936,000 over this period, accounted for half the improvement, a confidence vote for a sustainable expansion.

For the official unemployment rate, the 1.1 percentage point drop in the three months ended September has pre-pandemic precedent in the 1950s. This year, there’s also a voluntary aspect to the rise in labor resource utilization, especially with the cessation of special unemployment checks across many states shifting the opportunity cost, shall we say, to collecting a paycheck again.

We’re not dismissing the “disappointment” in September nonfarm payrolls (NFP). The 194,000 advance was light versus the 500,000 consensus. A closer look revealed literally and figurately got schooled. In a reversal of July’s massive seasonal upside in the sector, both public and private education headcounts declined. At 317,000, private employment did all the lifting, which gets you closer to the forecast with the caveat, via QI friend and labor guru Philippa Dunne, that the print is still 335,000 below the last three months’ private sector average.

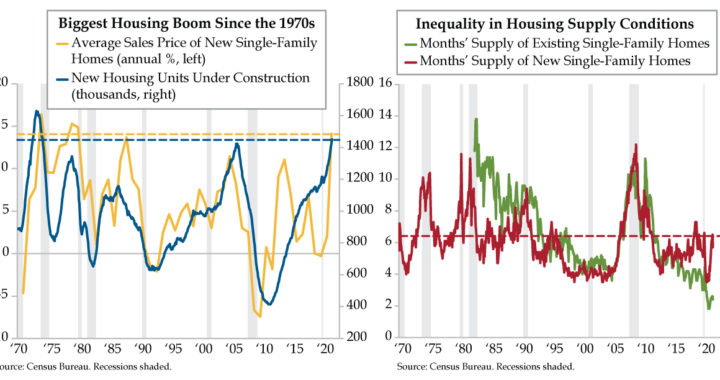

To Jerome Powell’s chagrin, the yield curve steepened, signaling the Fed should remain on track to launch its taper November 3rd. Not even the most dovish monetary policymaker can refute the 5.05 million total nonfarm jobs added thus far in 2021, a record in absolute terms for a first-nine-months stretch. With a remaining deficit of 4.8 million jobs still to be recovered, the biggest unknown is whether we’re as far away from full pre-pandemic employment levels as recent numbers would suggest. If this gap fills, the specter of persistent wage inflation could force the Fed to tighten more aggressively and expeditiously than markets anticipate.

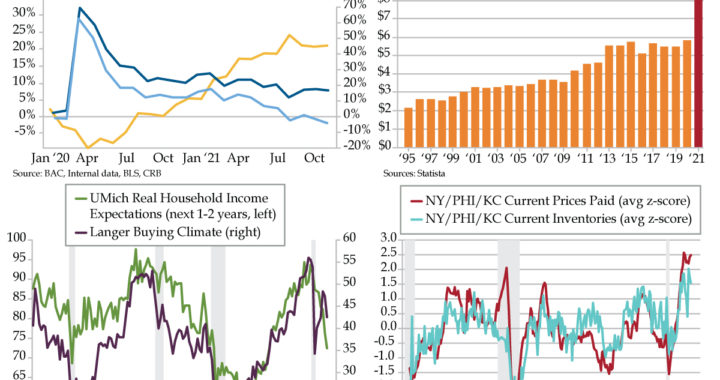

Last Tuesday, we used ISM’s production material commitment lead times to warn that a parallel with the 1970s energy crisis could be in the making. The Disco era also taught us that new inflation regimes require a confluence of factors, not just higher input and freight costs. We’d be remiss on this last point to omit signs that freight charges may be peaking. With a hat tip to QI fishing buddy Brent Donnelly, a reliable real-time way to track shipping is through the share prices of Cosco and Maersk, two of the world’s three biggest shipping companies. Of late, Cosco has failed to make new highs while Maersk did take out its June highs, but has since slipped below that level.

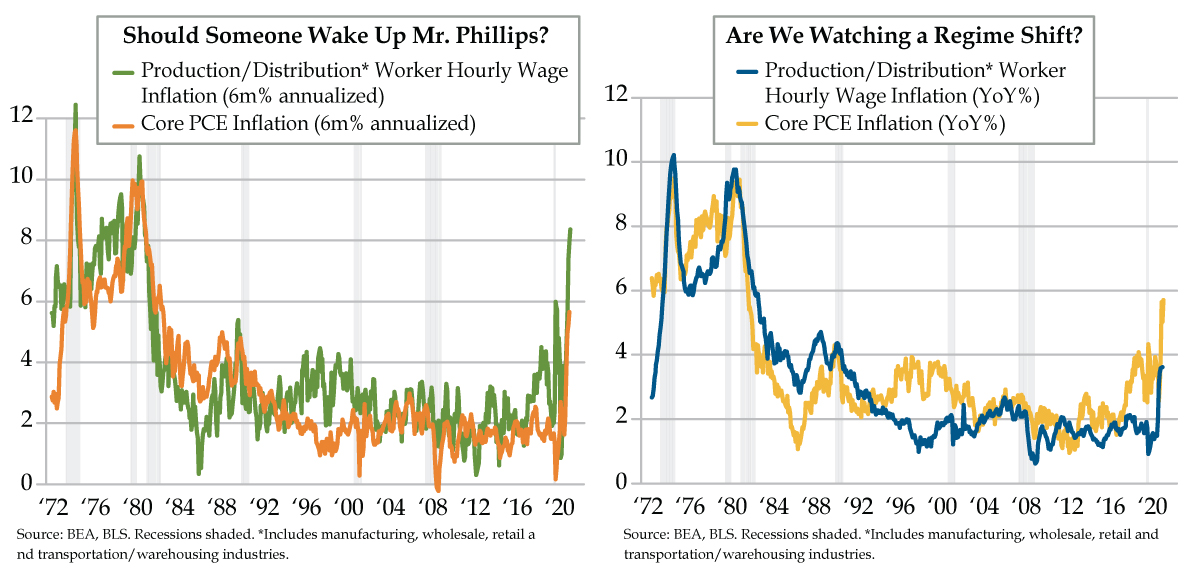

This potential tide turn does not negate the need to be alert to the missing ingredient of higher wages. At first glance, today’s charts may look like twins. Upon closer inspection, the left one depicts short-term trends (i.e., six months) and the right, the more conventional 12-month comparison.

Companies closest to the supply chain are battling the fiercest wage pressures. As defined, workers in production and distribution include the cyclical industries of manufacturing, wholesale, retail and transportation & warehousing. Usually, we track wages in these industries separately as they’re reported individually by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Aggregating them culminates in an 8.4% annualized gain in the six months ended September (green line), the highest since the early-1980s. Could the rise in the Fed’s preferred underlying inflation gauge, the core PCE price index (orange line), be attributable to more than a handful of anomalous items?

Wage data from payroll provider Paychex confirms the recent surge is more than a big company phenomenon. Paychex small business wage data through September showed three-month annualized gains of between 5.6% and 5.8% for the industries cited above. Over a 12-month span, the advances range between 4.2% and 4.7%. The asterisk is these levels are margin killers and could flag employers hitting their pain thresholds, which is also evident in persistently high hours worked, which indicates an unwillingness to take on more workers by squeezing more out of existing employees. Per Dunne, hiring healing still has a long haul ahead: “To get back to February 2020’s Employment to Population Ratio of 61.1%, we’d need to add another 6.4 million jobs.”

A chat with a high yield portfolio manager by QI’s Dr. Gates bound the macro to the micro, which is essential to making inflation persistence stick. Think of the python that ate not one, but three pigs — material, transport and wagecosts.” Perhaps